How I Almost Blew My Early Retirement — And Fixed It with Smarter Asset Allocation

What if the plan you trusted to fund your early retirement was quietly setting you up for failure? I thought I was on track—until a market dip exposed serious flaws in my portfolio. Turns out, asset allocation isn’t just about growth; it’s about survival. This is how I caught my mistakes, rebalanced with clarity, and built a more resilient path to financial freedom—without gambling on returns or chasing hype. The journey to retiring early is often sold as a story of discipline, sacrifice, and smart investing. But behind the success stories are quiet warnings—about portfolios that looked strong on paper but collapsed under pressure, about retirees who ran out of money sooner than expected, and about confidence that evaporated when markets turned. My story is not unique, but it’s personal. And if you’re planning to leave the workforce early, it might just save you from the same mistake.

The Dream and the Danger of Early Retirement

Early retirement has become more than a financial goal—it’s a cultural aspiration. Fueled by online communities, blogs, and social media, thousands of people are aiming to leave traditional work behind by their 40s or 50s. The appeal is understandable: more time with family, the freedom to travel, the ability to pursue passions without the constraints of a paycheck. For many, it represents a reclaiming of life from the grind of long commutes, office politics, and burnout. But beneath this dream lies a complex financial reality that is often underestimated. Retiring early doesn’t mean the end of financial responsibility; it means the beginning of a much more delicate balancing act.

The primary challenge of early retirement is longevity. When you stop earning a salary at 45, your savings must stretch for 40, 50, or even 60 years. That’s a vastly different timeline than someone retiring at 65 with an average life expectancy of 85. The longer the withdrawal period, the greater the pressure on your portfolio to generate consistent returns while avoiding catastrophic losses. This is where two silent risks come into play: sequence-of-returns risk and inflation risk. Sequence-of-returns risk refers to the danger of experiencing poor investment performance early in retirement, especially during the first five to ten years of withdrawals. A sharp market decline at this stage can permanently reduce your portfolio’s ability to recover, even if markets rebound later.

Inflation risk is equally insidious. Over decades, even moderate inflation—say, 2.5% per year—can erode purchasing power significantly. A dollar today will be worth only about 40 cents in 40 years if inflation holds steady. This means your portfolio must not only preserve capital but grow at a rate that outpaces inflation, all while funding your lifestyle. Many early retirees focus on achieving a high savings rate—aiming for 50%, 60%, or even 70% of income—but overlook how their investments are structured to handle these long-term threats. The assumption is often that strong historical market returns will continue, but past performance is no guarantee of future results, especially in a volatile or low-growth environment.

Emotional decision-making further compounds these risks. When markets fall, it’s natural to feel fear. But acting on that fear—selling stocks at a loss, pulling out of the market, or shifting entirely to cash—can lock in losses and derail decades of disciplined saving. The gap between theoretical risk tolerance and actual behavior is wide. You might tell yourself you can handle a 20% market drop, but when it happens and your net worth declines by $200,000 overnight, the emotional response can be overwhelming. This is why early retirement planning isn’t just about math; it’s about psychology, discipline, and the structure of your portfolio. A well-allocated portfolio isn’t designed to maximize returns at all costs—it’s designed to keep you on track, even when markets are unpredictable.

My Wake-Up Call: When My Portfolio Stumbled

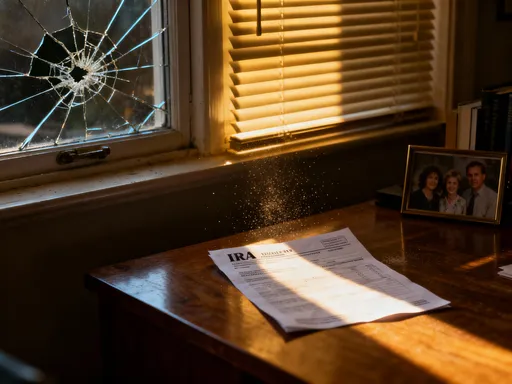

In 2020, I believed I was on solid ground. After 15 years of aggressive saving, I had accumulated enough to cover 25 times my annual expenses—a common benchmark for early retirement. My portfolio was heavily weighted in equities, with about 70% in U.S. stocks, including a significant portion in high-growth tech companies and sector-specific ETFs. Another 20% was in international equities, and the remaining 10% was split between bonds and cash. On paper, this looked diversified. I told myself I was a long-term investor, that volatility was normal, and that I could ride out any downturn. But when the market dropped sharply in early 2022, that confidence began to crack.

The trigger wasn’t a global crisis, but a combination of rising interest rates, inflation concerns, and tightening monetary policy. Growth stocks, particularly in the tech sector, were hit hard. My portfolio lost nearly 30% of its value in just six months. What made it worse was that I had recently begun testing early retirement, reducing my work hours and starting to draw small amounts from my investments. Seeing my account balance shrink while pulling money out created a deep sense of anxiety. I started questioning every decision: Was early retirement a mistake? Had I retired too soon? Was my entire financial plan built on false assumptions?

I almost made it worse by reacting emotionally. There were moments when I considered selling my remaining stocks and moving everything to cash. I read articles warning of a prolonged bear market, and for a brief period, I entertained the idea of shifting to stable-value funds or even holding physical gold. Fortunately, I paused. I reached out to a fee-only financial advisor, someone with no incentive to push products, and asked for an objective review. What I learned was sobering: my portfolio was not truly diversified. While I had exposure to different sectors and regions, nearly all my assets were tied to equities, which meant they were highly correlated—when stocks fell, almost everything fell together.

The advisor helped me see that my asset allocation didn’t match my risk capacity or my withdrawal needs. I had optimized for growth, but not for stability. I had ignored the importance of non-correlated assets—those that behave differently under stress. And I had underestimated how much my emotions would influence my decisions when real money was at stake. This moment was a wake-up call. It wasn’t just about recovering losses; it was about rebuilding a strategy that could withstand not just market cycles, but human behavior. I realized that financial resilience isn’t about avoiding downturns—it’s about designing a portfolio that allows you to stay the course, even when everything feels uncertain.

Asset Allocation: More Than Just Spreading Risk

Asset allocation is often described as the most important decision an investor makes—more impactful than stock picking or market timing. And for good reason. Studies have shown that over 90% of a portfolio’s long-term returns are determined by its asset mix, not individual security selection. But what exactly is asset allocation? At its core, it’s the strategic division of investments across different asset classes—such as stocks, bonds, real estate, and cash—based on goals, time horizon, and risk tolerance. For early retirees, this process is even more critical because they face the dual challenge of generating returns and managing withdrawals over a long period.

True diversification goes beyond simply owning different types of stocks. It means holding assets that respond differently to economic conditions. For example, when inflation rises, stocks may struggle, but commodities like gold or real assets like real estate investment trusts (REITs) may hold their value. When interest rates increase, bond prices typically fall, but short-duration bonds or Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities (TIPS) can offer better protection. A well-allocated portfolio includes a mix of assets that don’t move in lockstep, reducing overall volatility and improving the odds of consistent returns.

Geographic diversification is another key element. While U.S. markets have outperformed over the past decade, history shows that leadership rotates. In the 1980s and 1990s, Japanese equities were the darlings of global investing; in the 2000s, emerging markets took the spotlight. Relying too heavily on one country or region increases concentration risk. By including international developed and emerging market funds, investors can capture growth from different parts of the world while reducing dependence on any single economy.

The role of bonds in a portfolio is often misunderstood, especially by early retirees focused on growth. Bonds are not just for conservative investors—they serve as ballast. During equity market declines, high-quality bonds often hold their value or even appreciate, providing a source of stability. They also generate regular income, which can be used to fund withdrawals without selling stocks at a loss. The key is to match bond duration with your time horizon and interest rate outlook. Long-term bonds are more sensitive to rate changes, while short- and intermediate-term bonds offer more predictability.

Finally, asset allocation must be personalized. A 30-year-old with decades until retirement can afford to take more risk, while a 50-year-old entering early retirement needs a more balanced approach. The goal is not to eliminate risk, but to manage it in a way that aligns with your financial needs and emotional comfort. This means revisiting your allocation regularly, especially after major life events or market shifts. A static portfolio may have worked in a bull market, but it can fail when conditions change. Dynamic, intentional allocation is the foundation of long-term success.

Common Pitfalls That Sabotage Long-Term Portfolios

Even well-intentioned investors fall into traps that undermine their long-term success. One of the most common is overconcentration. This happens when too much of a portfolio is tied to a single asset, sector, or company. A classic example is someone who works in the tech industry and invests heavily in their employer’s stock. While this may seem like a vote of confidence, it creates double exposure: if the company struggles, both income and investments are at risk. The collapse of Enron is a stark reminder of how quickly concentrated wealth can disappear.

Another widespread mistake is chasing performance. Investors often buy into asset classes after they’ve already risen significantly, hoping to capture more gains. This leads to buying high and, inevitably, selling low when the trend reverses. The cryptocurrency boom of 2017 and the AI stock surge of 2023 are recent examples. Many who entered late suffered steep losses when the markets cooled. Past performance is not indicative of future results, yet the human brain is wired to expect trends to continue. This cognitive bias—known as recency bias—can lead to poor timing and suboptimal returns.

Fees are another silent killer. While they may seem small—0.5%, 1%, or even 2% annually—they compound over time and can erode a significant portion of returns. A fund with a 1% expense ratio can cost an investor tens of thousands of dollars over 30 years compared to a low-cost index fund with a 0.03% fee. The difference may not be noticeable year to year, but over decades, it’s substantial. This is why low-cost index funds and ETFs are often recommended for long-term investors—they provide broad market exposure at a fraction of the cost.

Failing to rebalance is equally damaging. Over time, some assets grow faster than others, causing the original allocation to drift. A portfolio that started as 60% stocks and 40% bonds might become 75% stocks after a bull market. This increases risk without the investor realizing it. Rebalancing—selling high-performing assets and buying underperforming ones—forces you to “buy low and sell high,” a principle that’s easy to say but hard to practice. Without regular rebalancing, a portfolio can become unintentionally aggressive, leaving it vulnerable to downturns.

Behavioral biases also play a major role. Confirmation bias leads investors to seek information that supports their existing beliefs, ignoring contradictory evidence. Loss aversion makes people feel the pain of a loss more intensely than the pleasure of an equivalent gain, leading to overly conservative decisions after a market drop. These psychological tendencies are natural, but they can be managed through discipline, education, and a well-structured plan. Recognizing these pitfalls is the first step toward avoiding them.

Building a Resilient Portfolio: Principles Over Predictions

No one knows what the future holds. Markets can be unpredictable, economies can shift, and black swan events can disrupt even the best-laid plans. But uncertainty doesn’t mean helplessness. A resilient portfolio isn’t built on forecasts; it’s built on timeless principles. The first is simplicity. Complex strategies often fail because they rely on too many assumptions. A portfolio based on low-cost, broadly diversified index funds is easier to manage, less prone to error, and more likely to deliver consistent results over time.

Global diversification is another cornerstone. Instead of betting on one country or region, a resilient portfolio includes exposure to U.S. and international markets, both developed and emerging. This spreads risk and increases the chances of capturing growth wherever it occurs. Research shows that over long periods, no single market consistently outperforms, so owning a slice of everything reduces the risk of missing out or being overly exposed to a single downturn.

A strategic mix of growth and income-producing assets is essential for early retirees. Stocks provide long-term appreciation, while bonds, dividend-paying equities, and real assets generate cash flow. The exact ratio depends on individual circumstances, but a common starting point is a 50/50 or 60/40 split between equities and fixed income. As retirement progresses, this mix can be adjusted based on market conditions and spending needs.

Alternative assets—such as real estate investment trusts (REITs), commodities, or even private credit—can add another layer of diversification. REITs, for example, offer exposure to real estate without the need to buy property directly. They tend to have low correlation with stocks and can provide steady dividends. Commodities like gold may act as a hedge against inflation, though they don’t generate income and can be volatile. The key is to use alternatives in moderation—typically 5% to 10% of the portfolio—and with a clear understanding of their role.

Discipline is the final, and perhaps most important, element. A resilient portfolio requires consistency. It means sticking to your allocation through market ups and downs, rebalancing regularly, and avoiding emotional decisions. It means focusing on what you can control—savings rate, spending habits, fees, and diversification—rather than trying to predict the unpredictable. Over time, this disciplined approach compounds, not just in wealth, but in peace of mind.

Managing Withdrawals Without Running Out of Money

One of the biggest fears of early retirement is outliving your savings. Unlike traditional retirees who may rely on Social Security or pensions, early retirees often depend entirely on their investment portfolios for income. This makes withdrawal strategy critical. The most famous rule of thumb is the 4% rule, developed in the 1990s by financial planner William Bengen. It suggests that withdrawing 4% of your initial portfolio balance each year, adjusted for inflation, gives you a high probability of not running out of money over a 30-year retirement.

However, the 4% rule has limitations. It was based on historical U.S. market data and assumes a specific portfolio mix (typically 50% to 75% stocks). In today’s environment of lower expected returns and higher valuations, some experts argue that a 3% or 3.5% withdrawal rate may be safer, especially for those retiring early. Moreover, the rule doesn’t account for flexibility. Life isn’t a spreadsheet—some years you may spend more, others less. Rigidly sticking to inflation-adjusted withdrawals can lead to trouble if markets are down.

Dynamic withdrawal strategies offer a more adaptive approach. These methods adjust spending based on portfolio performance. For example, in years when the market is strong, you might allow for a modest increase in spending. In down years, you reduce discretionary expenses—delaying a vacation, postponing a home renovation, or cutting back on dining out. This flexibility can dramatically extend portfolio longevity. Studies show that even small spending adjustments in bad years can improve success rates by 20% or more.

Another method is the floor-ceiling approach, where you set a minimum (floor) and maximum (ceiling) withdrawal amount. As long as your portfolio stays within a healthy range, you withdraw a base amount. If it drops below a threshold, you reduce spending; if it grows significantly, you may allow for more. This provides both security and the ability to enjoy gains when they occur. The key is to build flexibility into your lifestyle, not just your financial plan. Having non-essential expenses that can be scaled back gives you control and reduces stress.

Staying on Track: Monitoring, Rebalancing, and Mindset

A financial plan is not a one-time event. It’s an ongoing process that requires attention, maintenance, and emotional resilience. Regular monitoring—quarterly or annually—is essential to ensure your portfolio stays aligned with your goals. This doesn’t mean obsessing over daily market moves, but taking a step back to assess performance, allocation, and life changes. Did you have a child? Buy a home? Experience a health issue? These events can affect your financial needs and risk tolerance, requiring adjustments to your strategy.

Rebalancing is a critical part of this process. Over time, market movements cause your asset allocation to drift. If stocks have performed well, they may now represent a larger share of your portfolio than intended, increasing your risk exposure. Rebalancing brings your portfolio back to its target mix by selling some of the outperforming assets and buying more of the underperforming ones. This enforces a disciplined, contrarian approach—selling high and buying low—without requiring market predictions.

Automation can help reduce emotional interference. Setting up scheduled rebalancing, automatic contributions, or income ladders (where bonds mature at regular intervals to provide cash flow) can take the guesswork out of investing. These systems create structure and reduce the temptation to react impulsively to market news. They also free up mental energy, allowing you to focus on life rather than constantly managing money.

Finally, mindset matters. Financial independence is not a destination; it’s a way of living. It requires patience, humility, and a long-term perspective. There will be market downturns, unexpected expenses, and moments of doubt. But with a well-constructed, resilient portfolio and a disciplined approach, you can navigate these challenges with confidence. The goal is not perfection, but progress. By focusing on principles over predictions, process over outcomes, and sustainability over speed, you can build a retirement that lasts—not just in years, but in peace of mind.